I have to be transparent about something—

I’m someone who absolutely cringes when the topic of optimism versus pessimism comes up.

If I had to fall into a particular camp, I technically trend more behaviorally on the side of an optimist1. However, in my deeply entrenched logic brain, I am almost always trying to be the “indifferent realist” in any given situation, which can give the outward impression to others (and sometimes even towards myself) that I am more of a pessimist.

When I hear people talk about optimism versus pessimism, I wear my practical pessimism badge proudly and tend to roll my eyes at anything that trends too far towards the Pollyanna view on life. I can feel myself rolling back my shoulders to puff my chest out and defend against the dreaded toxic positivity that some people in our culture seem to have latched onto so they can bright-wash everything2.

For me personally, my external pessimistic shell comes from a place of not wanting to be perceived as naïve, or stupid. I don’t want others to think that I don’t learn from my mistakes and I definitely don’t want to perceive myself as being someone who can’t learn from previous information.

Deep down inside, and behaviorally—no matter how hard I try to avoid it—my tender heart is actually steeped in both optimism and hope. It can be a very confusing place to learn how to hold both…which maybe you can relate.

However, regardless of my personal feelings around “optimism versus pessimism”, as we step into the new year—while I’m not really into making a full-blown resolution around anything, it has come back to my attention that pessimistic outlooks and frameworks take substantially more energy (with less desired output) than optimistic ones3.

If we’re stepping into a new year working to pursue The Art of Rest, there’s a great case to be made around shifting ourselves to be slightly4 more optimistic…or at least learning how to use optimism as an effective, everyday tool.

Let’s get into it.

Optimism and Pessimism are Habits

Dr. Martin Seligman has done a substantial amount of research in his career around optimism and pessimism. There isn’t enough space in this blog to get into the nitty gritty, but Seligman’s research more or less started while he was initially researching what is known as ‘learned helplessness’. Learned helplessness is essentially a phenomena that occurs when animals are subjected to pain for a long period of time5. At first, all animals will do whatever they can to try to avoid, escape, or change this pain. However, if the pain persists long enough6, instead of continuing to try and change their circumstances to get away from the pain—eventually, animals will surrender into the pain and stop trying to escape. Essentially, the animals (or humans) who find themselves in a setting of learned helplessness have lost their sense of agency.

Learned helplessness has many implications for tons of areas of research. It overlaps with attachment theory, motivation research, and trauma research.

As it relates to pursuing more restful lives—we’ll be looking at how we can identify habits of pessimism and optimism, consider how they might be impacting our world, and shift them gently towards some optimism to regain our sense of agency.

It is from this sense of agency we are able to move more consistently towards choosing a life with more rest, creativity, and connection with ourselves and others. We are also more likely to try again if we don’t get it right the first time.

In essence, we don’t get rid of adversity, but we do find more ease in navigating through it.

Defining Optimism and Pessimism

According to Seligman’s research a pessimist will:

have a more “fixed” mindset—believing circumstances will last a long time, and are not apt to change

tend to internalize setbacks

give up more easily and give up more often

experience more frequent and severe periods of depression

tend to perform worse (than optimists) in school, work, and athletic settings

tend to have worse health outcomes

Whereas optimists will:

see setbacks as temporary and circumstantial

tend to externalize setbacks

tend to lean into non-linear accomplishments

re-orient difficult feelings

tend to perform better in school, work, and athletics

tend to exceed expectations of aptitude tests

tend to have better health outcomes—including living longer total years of life

Now, if you orient your thinking more pessimistically (or perceive yourself to be more pessimistic), you might be reading this list and already have some critical self-talk going on.

“Oh shit, I identify with the pessimist. I’m definitely going to die sooner, suck at my career, and push away everyone I love.”7

I want to gently remind you that, these tendencies of optimism and pessimism are changeable, shiftable, and malleable. Some of them come up more strongly at different chapters of our lives. Others might have more to do with our inherent temperament or life-circumstances growing up. Others still, could emerge when we’re around certain groups of people more than others.

I won’t lie and say shifting our thought habits are as equally and as easily changeable in all people—they aren’t. Some people will have to work harder than others to shift some of these habits, and they are shiftable. Nobody is sentenced to being a hopeless pessimist.

Seligman’s research (along with many, many others) has demonstrated a body of literature that optimism can be learned.

Shifting Towards Optimism

Optimism Techniques Aren’t Useful For Everyone Equally

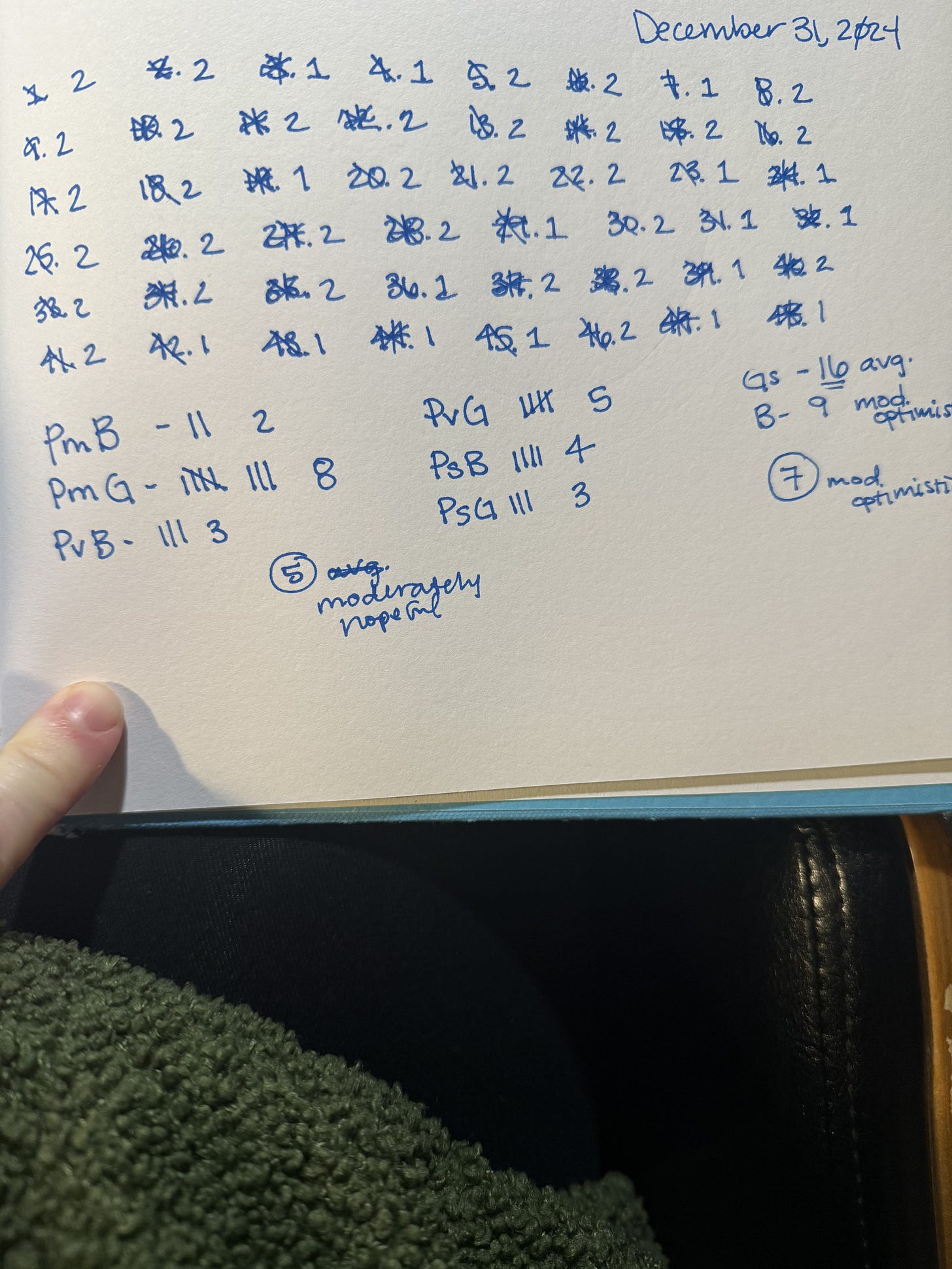

First of all, if you’re curious about what your actual Optimism scores currently are, you can take the test here.8 And I’ve got some additional nerdy information about this scale in the footnotes here.9

In general, it’s first and important to check in with yourself. Do you actually even need to be more optimistic in your life right now? If your scores on the Optimism test are average or trend towards the side of more optimistic…honestly, you’re probably good to give yourself a cute little pat on the back and move forward. No need to beat yourself with the stick of perfection. If you didn’t take the test but you feel good about how you’re navigating the world? Same logic applies. Read the rest of this article10, and then move on with your day!

Seligman also recommends checking in with yourself with a few other questions:

Do I get discouraged easily?

Do I fail more than I think more than I should?

Do I get depressed more than I want to?

Am I in a situation where I need to achieve something specific?

Am I in a situation that is chronic and has a long-term health outcome?

If your answer to any of these questions is “yes,” it might be worth putting some specific techniques into place.

Some Specific Optimism Techniques

Most of the techniques to shift towards a more habitually optimistic outlook falls under the category of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). In it’s most simple terms we’re watching the patterns of our thoughts, noticing what those thoughts mean to us, and then noticing how we behave based on those thoughts and meanings we make of them. Seligman proposes a very specific formula for moving through this process by inviting us to notice the:

Adversity - What we’re bumping up against

Beliefs - the thoughts, beliefs, and stories that show up when we encounter the adversity

Consequences - how we behave, or the implications the aforementioned beliefs have on us

The evidence-based protocol recommends keeping a diary of this chain of events for 3 or so days, or with 5 major incidents. After familiarizing ourselves with this process and understanding the embodied ways this series of events uniquely occurs for us—Seligman offers two major techniques to begin shifting towards optimism. Distraction and dispute.

Distraction from Pessimism

Distraction is often the first line of defense when we notice unhelpful pessimistic thinking. Typically the most effective process for distraction looks like:

Noticing the pessimistic thought process

Interrupting the thought as quickly as possible

other CBT techniques here like saying “stop” or

snapping oneself with a rubberband

Pairing the interruption by a grounding practice to re-orient the body

sensory exploration with the immediate environment11

calling to mind a very specific imagery that invites a sense of agency and safety

shaking parts of the body or dropping into your heels several times

Write down the worry/pessimistic thought

Set a time to think about it later

This is often the best technique when you have to perform something in the moment and do not have time to explore the pessimistic thought further. This however, is not the most effective of the two methods.

Disputing the Pessimism Works Best

If we’re wanting to shift pessimistic thinking towards optimistic thinking long term, taking the time to dispute the pessimistic thought is far more effective, and more enduring over time. When disputing the pessimistic thought it’s important to:

Noticing the pessimistic thought process

Interrupting the thought as quickly as possible (optional with CBT methods)

other CBT techniques here like saying “stop” or

snapping oneself with a rubberband

Learn how to argue with yourself about the particular details in the pessimistic thought to bring in a more objective viewpoint that emphasizes that the discomfort of the adversity is temporary and doesn’t have enduring and permanent meanings about your character. Some tricks for this are to

take stock of what you can and cannot control within the moment of adversity

reframe the adversity in a way that is less destructive

check in on the implications of what you think your beliefs about this adversity mean and decatastrophize those beliefs one at a time

To take this technique and make it even more effective, the best way to solidify this in the mind is to practice disputing your own internal dialogue with a friend you trust to ‘role play’ being the voice of your inner critic

This helps externalize the beliefs and

Creates a sense of connection, sympathy, and co-regulation between you and another person while you explore these beliefs.

In other words—when we are working on disputing the pessimistic thought process, we are working towards being more self-compassionate.

Can We Be Too Optimistic?

I’ll always let you make up your own mind, but my personal opinion is resoundingly yes.

Seligman’s research also says, yes, too much optimism can certainly be a thing.

We want to remember that while these scales and tools are helpful to orient us towards the trends in our behavior—these are not tools to become familiar with and then confuse them as cause-and-effect phenomena. If we begin to shift all of our thinking towards blaming external events and people for our adversities—we might feel better in a moment, and bounce back more quickly…but we also run the risk of becoming an unaccountable asshole with a lack of integrity. We might also run the risk of not learning valuable lessons from our mistakes. As with anything, personal responsibility is also a key element to balance when integrating optimism as one of our many tools towards a more restful, creative life.

Seligman suggests, instead of getting too caught up in trying to change all of our thinking towards being fully optimistic, it is more useful to focus on changing our beliefs in permanence.

In addition to all of this, optimism isn’t appropriate for all circumstances and shouldn’t be thought of as a silver bullet. If you’re in situations that are:

inherently risky in a way that could severely impact life outcomes and basic needs

inherently abusive

hoping to center sympathetic listening and problem solving with other people’s lives

acute moments of grief

…it’s probably better to hope for the best, but behave as if you’re preparing for the worst. In these cases, pessimistic behavior can be a superpower, too.

Why I’m Applying Optimistic Tools in 2025

I don’t know about you, but I’ve got some tender and lofty dreams for the next year ahead. I’m excited to grow and stretch myself creatively and connectively, and I hope on doing that all by sharing vulnerably from the heart. That process inherently has setbacks, adversity, and self-doubt baked in. I don’t want the fear of those setbacks to get in the way of the exciting work I hope to share, the juicy connections I hope to make, or the crazy creative projects I hope to pursue.

I want to keep striving for a creative life, doesn’t have to be one full of burn out and hustle. Similarly, I want to continue creating a life of rest so I have more presence and energy to work directly on the creative world I want to see.

Maybe by this point in the article I’ve gotten a bit squishier and a tiny-bit more Pollyanna, but I hope you get to use the optimism to spring you towards whatever it is you want, too.

Thank you all for supporting my work in 2024.

I am so damn excited to keep growing and sharing with you in 2025.

As per usual—

Thank you for being here.

Here’s to another year,

Dagny Rose

This sub-section of The Art of Rest, is all about—you guessed it—The Rest.

As a trained sleep scientist and mindfulness teacher & researcher, here we explore the everything related to rest. Whether we are unpacking the newest evidence-based sleep health tips, exploring day-to-day tools for bolstering and protecting rest, or diving into a world of dreams, “The Rest” is going to regularly touch into what a restful life is, and how to move towards one5

Looking For A Personalized Way to Optimize Your Rest?

Exciting announcement! My books are now open again for the hibernation season! I am looking forward to giving winter guidance around sleep health & nervous system regulation around stress. I offer individualized 1:1 guidance for those who want to use rest as a way to expand their creativity to just need a tune up all the way towards those who are dealing with chronic rest related issues. Shoot me an email at dagnyrose@theartofrest.me to inquire about getting started.

Meaning, I’m willing to fail and try again under similar circumstances because I tend to have moderate levels of hope, believe that many circumstances and approaches are changeable, and have confidence in my own ability to change and grow rather than beliving certain parts of myself are “fixed” or certain parts of the world around me are “fixed”

“Life is HARD dammit, and by god, we better be honest about that when we’re navigating it for the sake of everyone! I want some god damn honesty when navigating life, not the sunshine and rainbows version!” ← The knee-jerk narrative that shows up in my head

I just want to name here that this entire article is basically a synopsis of Martin Seligman’s audio book “Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life” and leaned towards restful living.

Okay, the research actually says we should be growing optimism as much as we can, but I just want to give everyone permission to be as cranky as they want to be without pathologizing it, yano? Including myself. Especially myself.

Or sometimes, to a high intensity of pain for a short, but chaotic and unpredictable amount of time.

or is unpredictable, intense, or chaotic enough

Oh, is that only me who catastrophes this way? Never mind, carry on.

Like all psychology measures, these tests are imperfect and should not be used as a diagnostic tool unless you’re working with a professional. However, they can be an incredibly helpful educational and self-reflective tool to help you get curious about your own current process.

Seligman talks about 3 different dimensions of this particular scale: permanence, pervasiveness, and personalization. Permanence and pervasiveness are more indicative of what we will do, where as personalization is more about how we feel about ourselves in situations.

PmB (Permanent Bad) - scale looking at attitudes where people tend to:

Give up easily, believe causes of bad events are permanent, bad events will persist and continuously affect their lives versus, hold grudges, feel helpless for days or months after a setback

This subscale is looking at how permanent we believe causes of bad events are

PmG (Permanent Good) - scale looking at attitudes where people tend to:

believe good things that happen are more permanent features of the world, try harder after they succeed

PvB (Pervasiveness Bad) - scale looking at attitudes where people tend to:

Troubles and adversities infect every other area of life

give universal explanations about adversity

catastrophize the event

PvG (Pervasiveness Good) - scale looking at attitudes where people tend to:

Troubles can be more easily ‘rightsized’ to a specific area of life, even if an important aspect is suffering (divorce, job loss, etc), other areas remain insulated from negative thinking.

Specific explanations about adversities are attributed to the specific event

believe good events will enhance all other areas of their lives

PsB (Personalization Bad) - scale looking at attitudes where people tend to:

blame ourselves

have lower self esteem

PsG (Personalization Good) - scale looking at attitudes where people tend to:

blame circumstances or other people (lol)

have higher self esteem

Hope (combines pervasiveness and permanence scales)

This often helps us locate how much agency we feel we have at any given point

and share it, of course. As a small business owner, I cannot express enough how much this helps me out ;).

What are 5 things you can see of a certain color? What are 4 different textures in the room? Can you locate 3 different sounds? What 2 different smells might you imagine are here? What is the taste in your mouth right now? Can you take 3 deep breaths from start to finish? etc.